What to Integrate, and What Not To

By Rob Kerr, M&A Integration Navigator at Kerr Integration

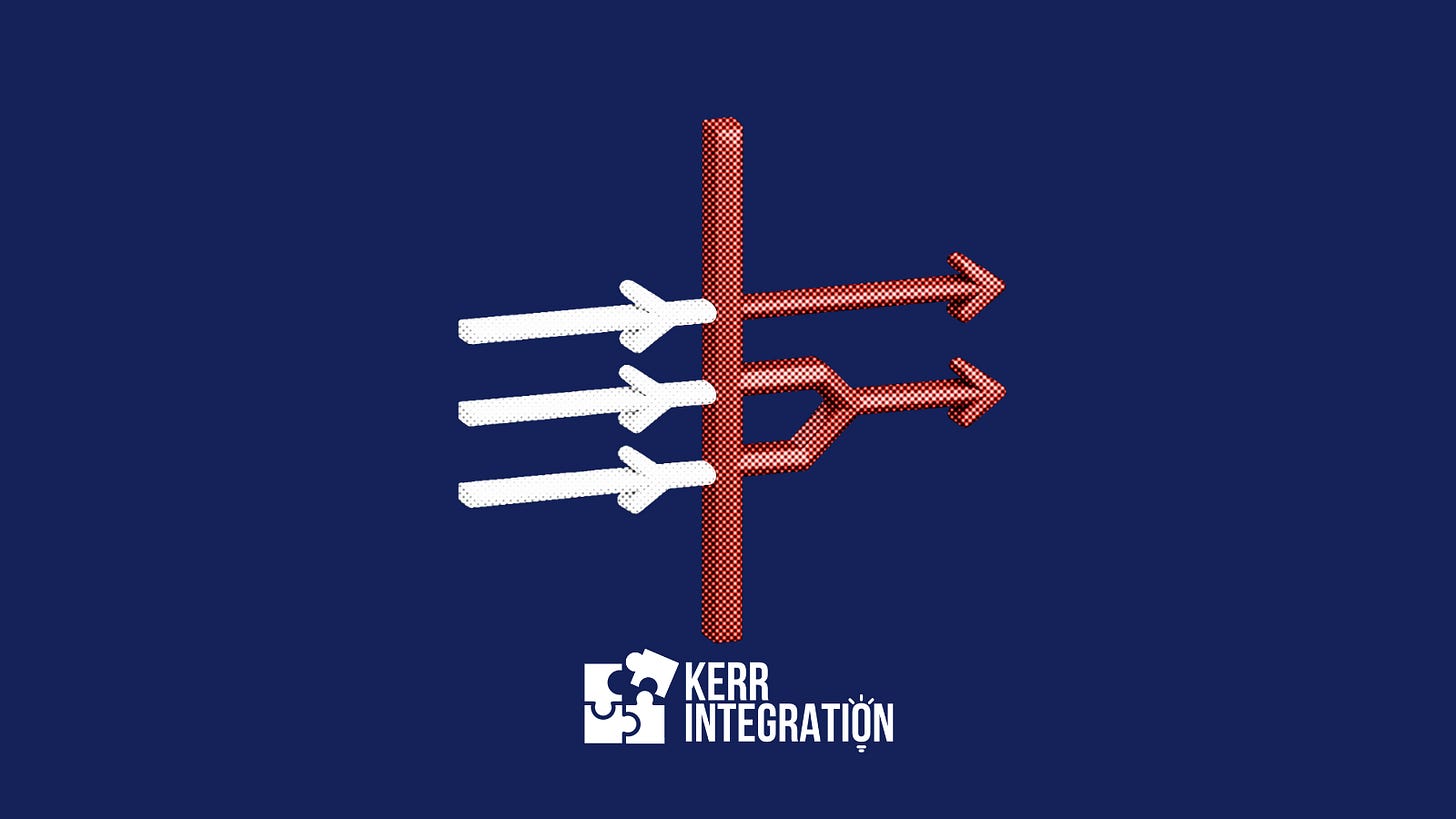

One of the most overlooked questions during post-merger integration is also the most fundamental: what should actually be integrated?

It’s tempting to assume the answer is “everything.” One team. One brand. One way of working. But that’s not always the right call, especially when creativity, differentiation, and momentum are part of the value.

I once supported an acquisition where multiple brands were brought into one group. Each had its own identity and internal creative team. All back office functions were integrated quickly and cleanly. By back office, I mean the core administrative functions that don’t generate revenue directly. This includes finance, HR, payroll, IT, procurement, and internal reporting.

But the creative and development teams were left alone. They were even encouraged to stay separate.

Each brand kept its own ways of working. Culture, tools and team dynamics were all preserved. Everyone knew they were part of the same company. When one team produced a big hit, it was celebrated more broadly across the group. Not as a cue to merge teams, but as a signal of what was possible. That success created a hunger in the other teams to deliver the next one. The separation was designed to drive performance.

It reminded me of how Sega operated in the 1990s, when it divided its game development into multiple in-house creative teams known as AM divisions. Each one had its own leadership, studio culture, and development priorities.

Daytona USA was created by Sega AM2, a team known for pushing technical boundaries. Shortly after, Sega Rally Championship was launched by Sega AM5, which had a different creative approach. Both games were major arcade hits, developed in close succession but by distinct teams. Internally, the teams were kept separate by design. Their creative styles and competitive energy were seen as assets, not inefficiencies.

Of course, internal competition has to be carefully managed. If it becomes visible to clients or suppliers, it can look messy or dysfunctional. And you need strong leadership to prevent duplication or friction. But in the right context, it can be incredibly effective.

This stuck with me because it was integration by design, not by default.

Integration isn’t about making everything the same. It’s about creating the conditions for value to grow. Sometimes that means full alignment. Sometimes it means leaving things intentionally distinct.

The skill lies in knowing the difference.

Explore Kerr Integration’s website to discover how we help turn post-deal complexity into clarity and control.